2.1 The Costs of Conflict

Analysis of data available from People Matter Surveys consistently indicates concerning levels of workplace conflict1, combined with low levels of confidence in traditional, formal grievance resolution processes. The data also shows that people experiencing workplace conflict have significantly lower levels of job satisfaction and engagement.

Researchers and practitioners have long suggested that unresolved conflict is among the largest reducible cost in organisations. Estimates suggest that the average Victorian public sector stress claim is $110,000. This is consistent with the average cost reported by the Australian Government’s medical insurer, Comcare.2

The Australian Institute of Management (AIM) has reported that between 30 and 50 per cent of a manager’s time is spent managing workplace conflict.3

The costs of unresolved conflict include:

- Individual distress: Mental and physical wellbeing, absenteeism, counter culture activities and ongoing dissatisfaction, irrespective of result

- Broken relationships: Lost productivity (‘presenteesim’), lost opportunities, declining trust and morale and increased disputation

- Organisational resources: Case management, recruitment and retention.

As can be seen from the above the costs of this unresolved conflict are many, ranging from individual distress, to broken relationships and strained organisational resources.

We know that a growing proportion of workers compensation claims are based on injuries related to stress, and much of that stress is associated with unresolved conflict.4 (Figure1)

While the research does not specifically refer to the term workplace conflict, it is reasonable to assume these findings are relevant to the issue of workplace conflict. Also, while there search did not differentiate between conflict-related stressors relating to contact with clients and co-workers, there is clear evidence that workplace conflict can result in significant costs.

Figure 1: Workers Compensation and stress

Research undertaken by WorkSafe Victoria has found that:

- Work-related stress is the second most common compensated illness/injury in Australia.

- Since 2001, stress related injuries have continued to make up a growing proportion of workers compensation claims (increasing year to year from 8% in 2000-01 to 10% in 2004-05).

- In Victoria, work-related stress, particularly in the public sector, has in recent times presented a growing percentage of workers compensation claims.

- Public sector workers account for a disproportionate share of work related stress (20% of claims, compared to 7% of claims by workers in other sectors).

- Roughly double the amount of compensation is paid to workers suffering from stress, compared to other injuries.

- Of 13 identified ‘key stress risks’, two (‘bullying’ and ‘interpersonal relationships’) were in the top 5.

2.2 Where is the Victorian Public Sector?

During the course of the project, it was identified that the need to manage organisational risk, as well as risk to an individual, is of high importance. This is illustrated in the case study ‘Building a business case for change’ at Appendix B.

Many of the issues resulting in complaints and grievances to the Public Sector Standards Commissioner need not have escalated into unresolved conflict. Analysis suggests that many of the underlying issues could have been resolved through early intervention and informal approaches.5

In 2001, a major report on conflict management systems argued that organisations typically evolve through four phases in their approach to workplace conflict6 as shown here.

1. No defined institutional processes for dispute resolution.

2. Rights-based grievance procedures are introduced.

3. ‘Interest based’ processes (usually involving mediation) supplement rights-based processes.

4. Focus moves beyond responding with grievance processes and mediation to:

- analysing and responding to root causes of conflict

- strengthening relationships through positive communication.

The sector is currently estimated to be at phase 2. The general consensus of project participants was that the sector is largely driven by a rights-based framework. Participants pointed to the relatively heavy use of the ‘review of actions’ provisions in the Public Administration Act 2004 and various enterprise agreements as evidence.

As a result, organisations have tended to develop a reliance on grievance procedures and arbitration, adjudication and appellate processes to deal with the number and range of cases. These approaches allow for a third party to determine who is in the wrong and to impose an official resolution. It should be noted however, that some organisations have commenced using mediation as a means of trying to resolve workplace conflicts.

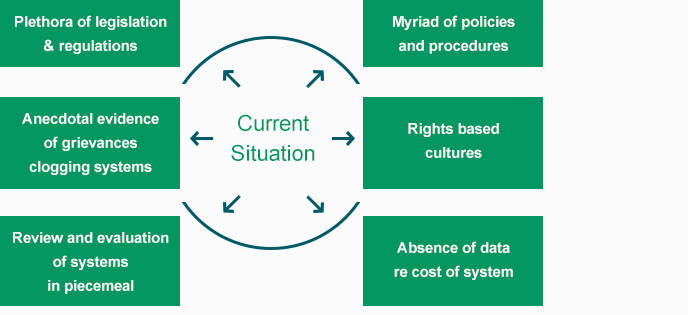

The diagram below provides a snap shot of some of the elements of current complaint handling systems.

Figure 2: Current approaches to conflict management in the Victorian public sector

2.3 The Road to Change

The Taking the Heat Out of Workplace Issues project started from the premise that most conflict cases could be handled with fewer resources and would generate less risk if organisations had better systems for handling disputes and conflict.

There is a strong business case to support this view – although quantifying actual and potential costs is not a simple task.

Many larger organisations record the number of formal grievances and the time required to address them. However, other costs are less easily measured: presenteeism, absenteeism, resignation, property theft and damage, illness related to chronic stress, and the effects of poor decision making.

Despite these challenges, feedback from those who are using new models for managing conflict like that on the following page suggests there is considerable value in of early, non-adversarial models of intervention such as mediation and facilitation.

Money Spent on Coaching Makes Business Sense

When I moved to a new workplace recently, I found a conflict case that had been festering for three years. I imported a methodology based on conflict coaching that I’d used successfully in my previous workplace.

I initially costed the resources that had been consumed on this case during the preceding three months before I used the coaching method and identified that two thirds of the cost of this case had been taken up with internal resource consumption (meetings, written updates) which consumed time but achieved nothing.

In comparison, now one third of the costs are being spent on external conflict coaching. This appears to be addressing and rectifying the issue at a fraction of the cost and risk.

Using non-adversarial approaches can substantially reduce the risk of damaging relationships, the cost associated with case management and the ripple effects of staff turnover, productivity loss and morale issues, by dealing with issues much earlier in the piece, rather than letting them fester.

– Project participant feedback, 2009.

Some organisations have found hard evidence to support the benefits of this new approach.

One organisation saved $50,000 a month by changing its conflict management model to one that focused on alternative dispute resolution processes.

Difficult cases were addressed using conflict coaching and mediation – this resulted in cases being resolved more quickly, used fewer resources and lowered the risk of expensive litigation.

The organisation estimated a related risk reduction of $150,000 a month.

The case study at Appendix B describes one organisation’s modelling and findings in more detail.

An approach based solely on ‘rights’ and formal grievances such as the one illustrated in Figure 2, can create particular ways of thinking about conflict and personal responsibility:

- The ‘arms length’ approach can easily reinforce the idea that someone else is responsible for the cause of the problem, and someone else is responsible for fixing the problem.

- Often, affected parties are not directly involved in the ‘resolution’ process.

- Because of the focus on ‘rights’, underlying and systemic issues are not always addressed.

Paradoxically, this means that the current systems used in the sector are both underused and overused: underused, because people avoid what they perceive to be an unfair, cumbersome system that might bring negative consequences; and overused, because we know that unresolved conflicts are clogging the system.

Footnotes

- In the form of bullying and harassment

- Comcare is the workers compensation insurer for the Australian Government.

- AIM, Management Today, August 2007

- WorkSafe Victoria (2007), Stresswise – Preventing Work-related stress: A guide for employers in the public sector

- Victorian Public Sector Commission (2008), Taking the Heat out of Workplace Issues Discussion Paper

- Designing Integrated Conflict Management Systems: Guidelines for Practitioners and Decision Makers in Organizations (2001) Cornell Studies in Conflict and Dispute Resolution (No.4), Martin and Laurie Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution, School of Industrial and Labor Relations & the Foundation for the Prevention and Early Resolution of Conflict (PERC), Cornell University.