It uses conflict management systems that integrate strong diagnosis (‘what is the cause of the problem?’) with appropriate decision making about the best response (‘is this best managed through adjudication by a third party, or can we resolve this better through mediation, a courageous conversation or facilitation?’).

A practical and achievable first step for sector organisations is to build an integrated conflict management model.

3.1 An Integrated Conflict Management Model

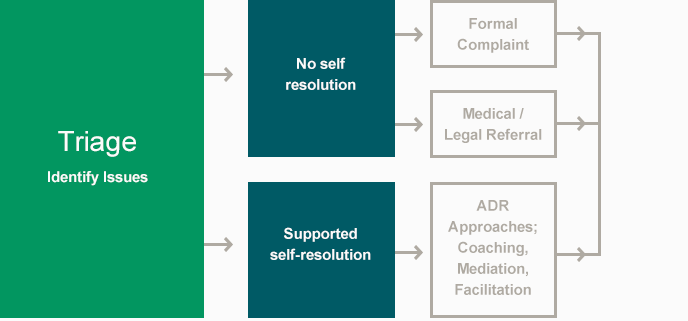

Each workplace has its own cultures, processes and traditions: this means conflict management systems will inevitably look different in every organisation. However, as Figure 3 shows, an integrated conflict management model has two key features.

First, it is always underpinned with a strong intake assessment system (triage, see Figure 3) when issues are raised. Second, it encourages alternative dispute resolution (with a strong focus on interests and needs of the people involved) approaches.

Figure 3: Integrated conflict management model

The model retains a place for formal grievance processes – but they are used only for specific disputes suited to formal complaints, or as a safety net.

An Integrated Conflict Management Model

- Provides early intervention through a triage or collaborative intake assessment system with multiple entry points for ease of access.

- Identifies root causes of problems in addition to symptoms, and shares this information to create change.

- Uses alternative dispute resolution methods (feedback, conversation, mediation, facilitation) that preserve workplace relationships by:

- addressing the needs and interests of parties – not just their rights

- encouraging self resolution, rather than emphasising a formal process.

- Incorporates preventative actions such as training and awareness raising.

Where Does this Leave Formal Grievance Processes?

Putting resources into alternative dispute resolution models does not do away with the need for grievance structures.

For example, certain situations demand formal processes be used: allegations of criminal or serious misbehaviour; situations where there is a lack of good faith and parties won’t cooperate; situations where public policy, procedural or legal issues arise, or where the welfare of individuals is threatened.

There is widespread acceptance, and a legal requirement, that organisations must have fair and effective systems for handling grievances. If someone claims that a law, standard or guideline has been breached, there must be an effective and fair system to test that claim. If a grievance handling system is not perceived as procedurally fair, it will itself generate grievances, and become part of the problem.

A conflict-resilient workplace uses adjudicated grievance processes when they are necessary; but prevents conflict escalating into formal grievances when early resolution is possible.

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) processes and techniques are useful in managing a range of situations from individual performance to the intellectually challenging or emotionally complex issues that can arise in working relationships.

The methods are informal, voluntary and don’t include litigation. While they are usually structured, they can be non-adjudicatory.

Importantly, they are based on four key tenets, that:

- the best decision makers in a dispute are usually the people directly involved;

- to effectively resolve a dispute, people need to hear and understand each other;

- disputes are best resolved on the basis of people’s interests and needs; and

- disputes are best resolved at the earliest possible time and at the lowest possible level.

Figure 4: Examples of ADR approaches

Commonly Used Processes to Promote Constructive Relationships

Feedback

Offering observations or helping someone to reflect.

Conversation

People talking to reach shared understanding and (possibly) commit to action.

Meditation

A third party helping to find mutual understanding and optimal action.

Facilitation

A third party helping a group to achieve a collective goal. This could involve workplace conferencing or what is known as appreciative inquiry.

Coaching

A third party works with an individual to help develop insights and clarity around resolving disputes and conflict.

Using the best process for the situation

The following table distinguishes a range of different situations, and presents corresponding structured processes for responding constructively1:

Figure 5: Choosing the best process option (Situation / Appropriate processes)

Disputed accusation

Investigation + adjudication

Managers needing to respond appropriately to disputes and conflicts

Conflict coaching and other managerial skills

Dispute between two parties

Mediation (assisted negotation)

Dispute or potential dispute between several parties

Facilitation (problem-solving, strategic planning, appreciative inquiry)

Specific-conflict with no dispute or many disputes

Group conferencing, transformative mediation

General conflict across an organisation

Managed change, training, coaching, mediation, facilitation

3.2 What Victorian Public Sector Leaders Can Do

Victorian public sector leaders can encourage managers and teams to use the companion guide to this report: Developing Conflict Resilient Workplace – a guide for managers and teams. This is a review tool to help managers and teams move toward an integrated conflict management model.

As well, they can support the use of alternative dispute resolution (ideally, as part of an integrated model), coordinate efforts to improve conflict management, and measure the actual and potential savings produced.

Support the Use of Alternative Dispute Resolution

Staff must be skilled, or experts brought in, if alternative dispute resolution is to be more widely used.

To do this, organisations can:

- promote skills development as part of a leadership capability framework (specifically, skills in feedback, conversation, mediation and facilitation)

- develop protocols for effective coaching; communicate the benefits of adopting a coaching approach; train staff in relevant methods

- build coaching into manuals and procedures to embed as part of an organisation’s responses to handling complaints and other issues

- create lists of internal and external consultants who can work as coaches, mediators and facilitators.

Coordinate Efforts

Often, different organisational divisions are responsible for different policies, and are seen to ‘own’ those policies. For example, Occupational Health and Safety may be seen to ‘own’ policies concerning workplace discrimination and harassment. This is a common structural impediment to developing an effective conflict handling system.

‘Grievances’ and ‘disputes’ might be managed by different divisions, encouraging the question: ‘in whose in-tray does this belong (who owns this case)?’ rather than ‘what’s the nature of the dispute’ and ‘who is involved?’.

Coordination will be needed to foster common principles and practices among divisions such as Human Resources, Occupational Health and Safety, Industrial Relations, Employee Relations, and Organisational Development.

Coordination is also required to produce a common system of case management, and to monitor cases across the organisation.

Organisational leaders need to coordinate an effort to articulate clear, concise organisational aspirations, to define the role of designated case managers, and to identify the requisite training for teams and managers.

Moving towards a fully integrated conflict management model with a focus on strong communications and relationships will need longer-term resource planning: the right people, the right programs, the right messages and the right budget.

The table below is based on ideas in Designing Integrated Conflict Management Systems (2001).

The right people

- A common vision from managers

- A representative body overseeing the system

- Independent third party advisors and facilitators within the organisation

- A coordinating office or mechanism

The right programs and processes

- Mechanisms for monitoring and evaluating the system

- Appropriate programs of learning and development

- Policies and practices that are consistent with a philosophy of conflict resilience

- Incentives embedded in organisational systems: performance appraisaland management

The right messages

- Communication strategy

The right budget

- Cost allocation that encourages early and effective conflict resolution

- Resources to implement and coordinate an effective system

Monitor Success

The business case for effective conflict management and prevention needs to be better developed and articulated across the sector.

Effective monitoring and measuring will tell us if a new approach to managing conflict represents a better return on investment than a focus on grievance processes.

How to present a business case (projected savings) and how to measure success following interventions, also remain two of the biggest challenges for individual organisations.

The case study at Appendix B of this report describes one model that has been used to quantify and measure success at the organisational level. The VPSC resources on people metrics2 are also relevant.

3.3 Beyond Integrated Systems – Conflict Resilient Organisations

Sector organisations with a strong integrated conflict management system will respond well to conflict by taking the heat out of workplace issues early.

Once an organisation begins to identify root causes of conflict in individual cases, managers can also look for patterns across multiple cases. They ask:

- What sort of early interventions could resolve the greatest number of problems?

- What could have prevented a situation from becoming problematic in the first place?

- What would it take for people in this organisation to have more constructive interactions, working relationships, and group dynamics?

- What would it take to shift organisational culture beyond responding to, and preventing, disputes and conflict?

- What initiatives would promote an organisational culture characterised by positive communication and working relations?

When conflict management is truly integrated in organisations, the result can be described less as an integrated conflict management system and more as a system to improve communication and workplace relations. This system will include dispute and conflict handling components, but the main focus will be on building and strengthening relationships. The result will be a conflict resilient organisation.

Figure 6 depicts a conflict resilient workplace. Appendix C describes the attributes of a workplace with reference to the three layers of the ‘conflict resilient workplace pyramid’.

Figure 6: The conflict resilient workplace pyramid

This diagram reflects an environment that is no longer dominated by a heavy reliance on grievance procedures. At the top of the pyramid (grievance procedures) formal processes are employed only in respect of allegations of criminal or serious misbehaviour; where there is a lack of good faith; situations where public policy, procedural or legal issues arise, or where the welfare of individuals is threatened.

The next stage denotes activity in an integrated model (of formal and alternative dispute resolution practices), characterised by intake assessment practices and an acknowledgment that responsibility for solving conflict is one shared between people involved (collaborative problem solving). Methods used for resolving interpersonal conflicts are usually those mentioned in Figure 4: feedback, conversation, mediation and facilitation. Typically the focus in this area is focused on preventing things from going wrong.

The pyramid’s foundation level signifies that the shift in culture is characterised by one where the dominant focus is on constructive communication (building and strengthening relationships) to help things go right.

There are a considerable opportunities for the sector to take the heat out of workplace issues as highlighted throughout this report. Most are relatively simple processes to implement.

To achieve significant improvements, reduce costs and provide early resolution, a whole-of-organisation change program is strongly recommended. The companion document to this report, ‘An implementation guide to developing conflict resilient workplaces’ provides a step-by-step methodology. We welcome your feedback on this report and are happy to provide further information and assistance.

Footnotes

- Adapted from D.B. Moore (2003) David Williamson’s Jack Manning Trilogy: A Study Guide, Sydney: Currency Press.

- A Guide to People Metrics; A dictionary of People Metrics