A note about the content on this page

The content on this page was developed in 2019 by the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA), on behalf of the VPSC, as part of the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander cultural capability toolkit for public sector workplaces. We are currently updating this content as an action in Barring Djinang: First Peoples Workforce Development Framework 2024 to 2028.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a shared history of colonisation and forced removal of their children. To be culturally competent, we must acknowledge and tell the truth about Australian history and its ongoing impact for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and we should understand how the past continues to shape lives today.

Before colonisation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people lived in small family groups linked into larger language groups with distinct territorial boundaries. These groups had complex kinship systems and rules for social interaction; they had roles relating to law, education, spiritual development and resource management; they had language, ceremonies, customs and traditions and extensive knowledge of their environment. In other words, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures were strong and well developed, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander communities were self-determining, and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children were nurtured and protected.

European colonisation had a devastating impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and cultures. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were subjected to a range of injustices, including mass killings or being displaced from their traditional lands and relocated on missions and reserves in the name of protection. Cultural practices were denied, and subsequently many were lost. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, colonisation meant massacre, violence, disease and loss.

Despite the past and present impacts of colonisation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship systems, customs and traditions still thrive, and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, families and communities remain strong and resilient. 1

There is a rich body of literature on the violent history of colonisation in Victoria including massacres, missions, segregation, deaths in custody and land rights.

Some sources you can access for information are:

- Deadly Story – History

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Timeline

Stolen Generations

‘The Stolen Generations are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who, when they were children, were taken away from their families and communities as the result of past government policies. Children were removed by governments, churches and welfare bodies to be brought up in institutions, fostered out or adopted by white families.

The removal of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children took place from the early days of British colonisation in Australia. It broke important cultural, spiritual and family ties and has left a lasting and inter-generational impact on the lives and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’2

The National Apology to The Stolen Generations

On the 13th of February 2008 the Prime Minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd delivered an apology to the Stolen Generations. The National Apology to the Stolen Generations came about as a recommendation from The National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal Children from their Families. It highlighted the suffering of Indigenous families under the Commonwealth, state and territory Aboriginal protection and welfare laws and policies.

The National Inquiry then led to the Bringing Them Home report which was tabled in Parliament on 26 May 1997. It contained 54 Recommendations on how to redress the wrongs done to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by the race-based laws and policies of successive governments throughout Australia.

Recommendations 5a and 5b suggested that all Australian Parliaments and State and Territory police forces acknowledge responsibility for past laws, policies and practices of forcible removal and that on behalf of their predecessors officially apologise to Indigenous individuals, families and communities.3

Watch the National Apology to The Stolen Generations

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Culture

There are many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and peoples. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures exist and thrive in a wide range of communities throughout Australia. The Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people you work with are not all the same—their culture, what they value and hold dear, how they live and make decisions and their relationships are diverse. As in Western and Eastern cultures, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures have characteristics they share and others that differentiate them, so it is important to avoid assumptions regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

While diversity exists across and within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural characteristics are part of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and unite Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through shared history and shared experiences. Understanding these cultural characteristics and appreciating their impact for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people today is a cornerstone of cultural competence.4

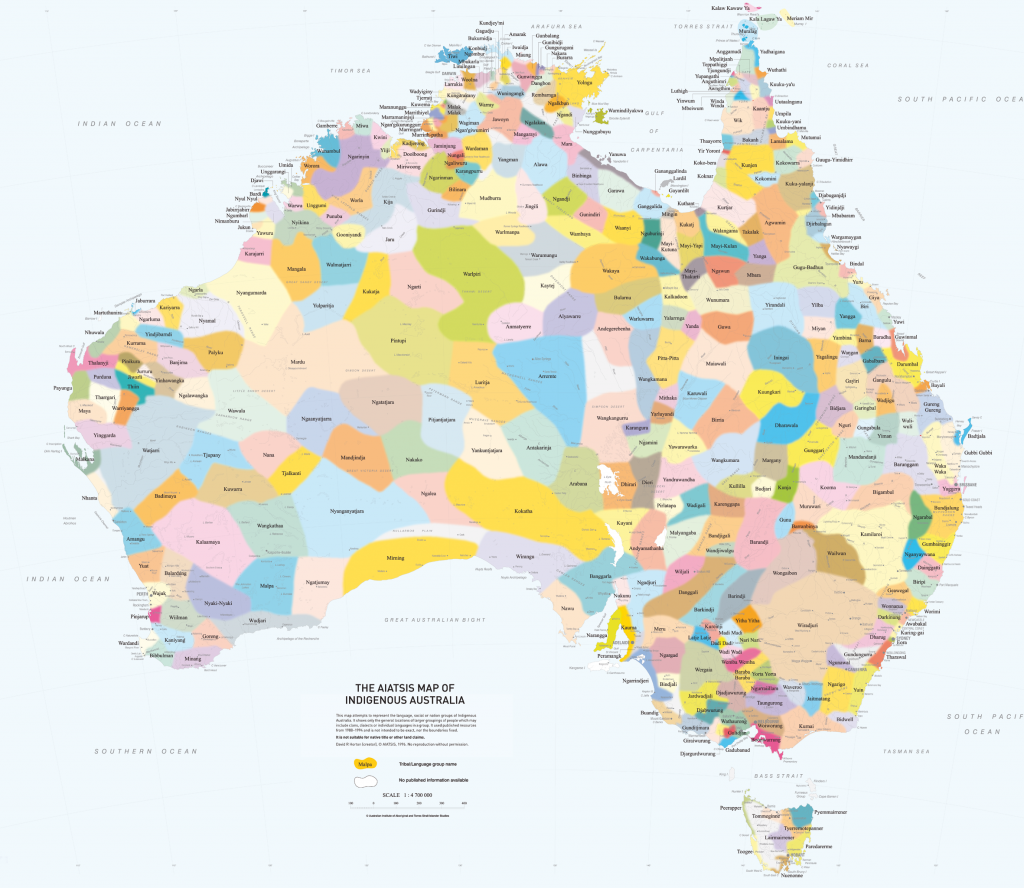

‘For thousands of years, the original inhabitants of Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people occupied the lands with very different boundaries than today, centred on intimate cultural relationships with the land and sea.

This map is an attempt to represent all the language, tribal or nation groups of the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people of Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups were included on the map based on published resources available between 1988 and 1994 which determine the cultural, language and trade boundaries and relationships between groups’.5

Explore the map in further detail.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Connections

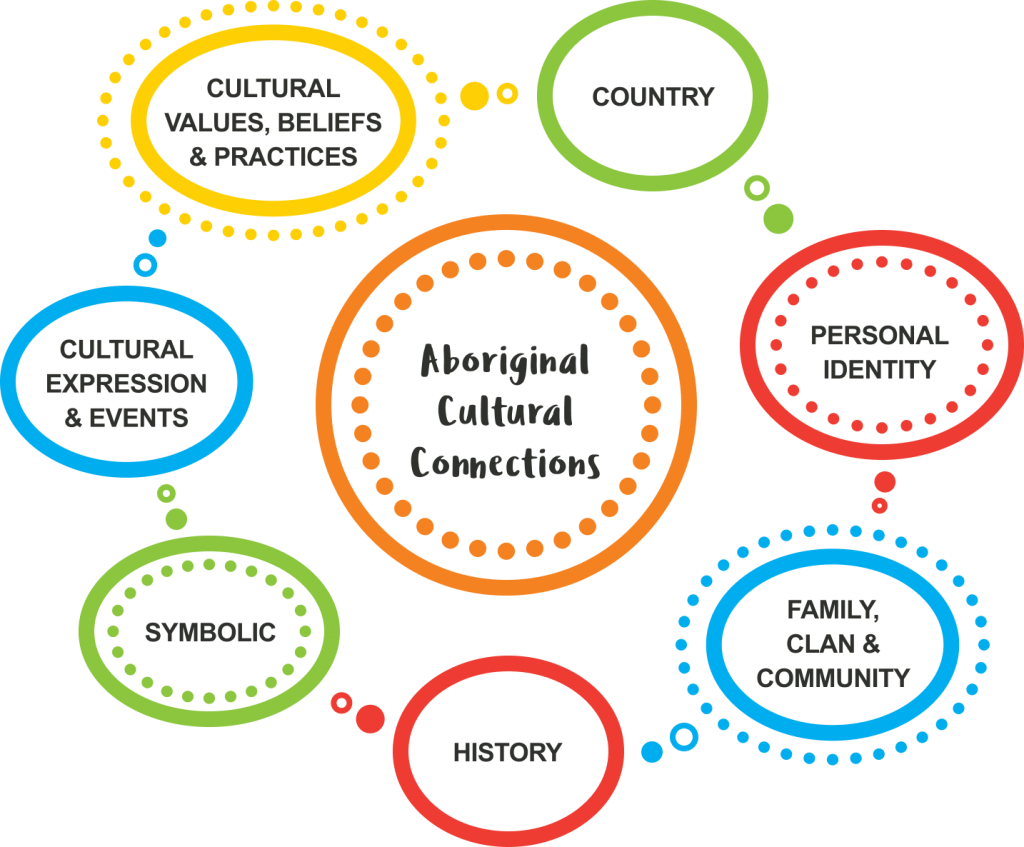

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, culture is the foundation upon which everything else is built.

Culture underpins all aspects of life including connections to family and community, connection to Country, the expression of values, symbols, cultural practices and traditional and contemporary forms of cultural expression such as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander language, ceremonies, cultural events, storytelling, dance, music and art. The following diagram highlights these important cultural connections:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Kinship Ties

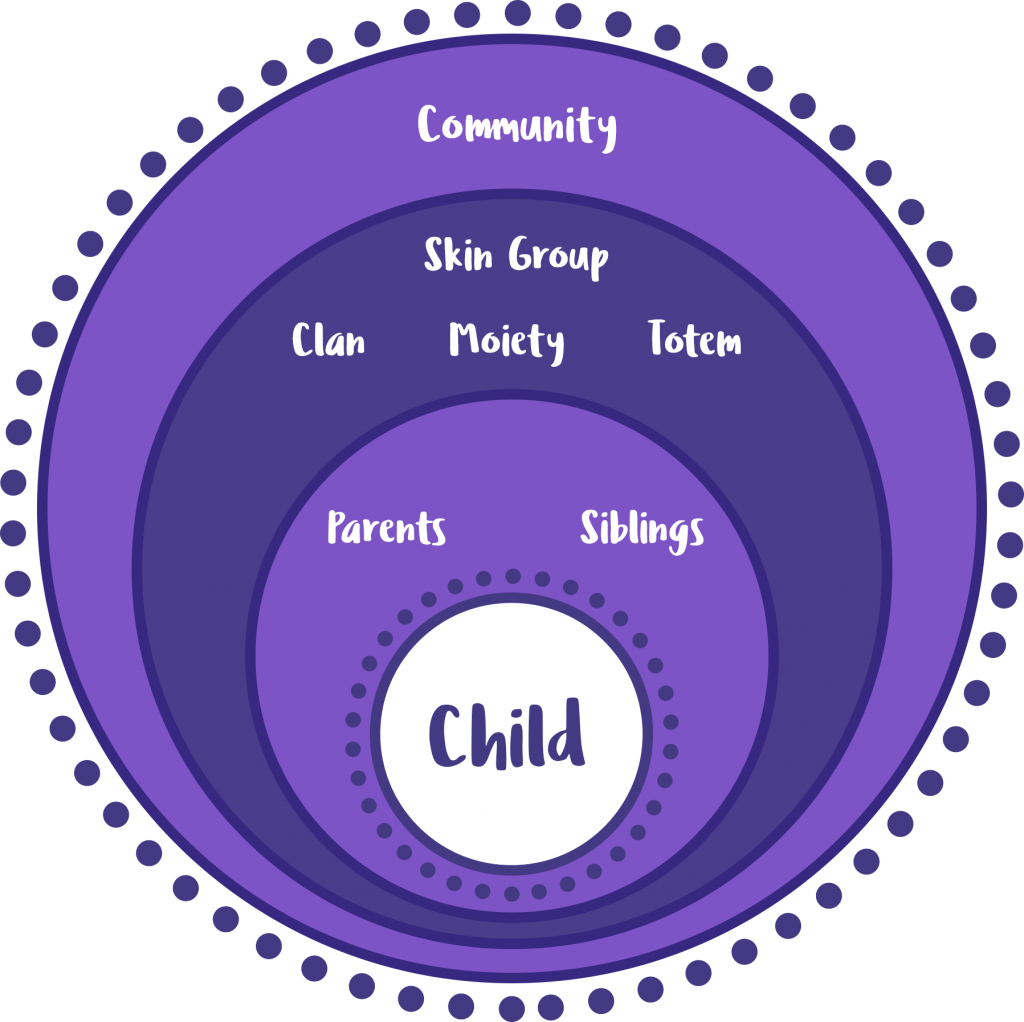

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people view individuals within a community holistically. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander understanding of the individual is in relation to the family, the community, the tribe, the land and the spiritual beings of the lore and dreaming. A person’s physical, emotional, social, spiritual and cultural needs and well-being are intrinsically linked—they cannot be isolated. The person is not seen as separate, but in relationship to and with others. An Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander perspective views:

- the person’s relationship to their whole family—not just to their parents and siblings

- the person’s relationship to their community—not just their family

- the person’s relationship to the land and the spirit beings which determine lore and meaning.6

Within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, kinship networks are based on relationships of blood, marriage, association and spiritual significance. An Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person has brothers, sisters, mother, fathers, uncles and aunts, who are additional to relationships by blood or marriage. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children understand that these people are important in their life—they are people who will support them and on whom they can rely—they are family. These relationships are maintained through involvement in community. Even if they see each other infrequently, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people describe a closeness that exists—‘like I saw her yesterday’. Each individual is important, has a role to play in the community and is accepted for both their strengths and limitations. Sharing is a strongly promoted value. There is a strong obligation to share if others are in need. The family, and one’s obligations to the family and community, are more important than material gain.7 The diagram below shows the key features of a traditional Aboriginal family structure.8

Respect for Elders

From a very young age, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are told about their relationships and links to others and are taught to show respect to their Elders. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, Elders play a vital leadership role.9

An Elder is an identified and respected man or woman within the community who has the trust, knowledge and understanding of their culture and permission to speak about it. They are often recognised as being able to provide advice, offer support and share wisdom in a confidential way with other members of the community, particularly younger members.

Some Elders are referred to as Aunty or Uncle, but you should only use these titles when given permission to do so – simply asking is the best way to find out if you can do so or not. 10

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Spiritual Relationship with the Land

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a deep connection with the land or Country, which is central to their spiritual identity. This connection remains despite the many Aboriginal people who no longer live on their land. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people describe the land as sustaining and comforting, fundamental to their health, their relationships and their culture and identity.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, their traditional Country and what it represents in terms of their history, survival, resilience and cultural and spiritual identity gives them much to take pride in. In the dominant Australian culture, land is thought of as a commodity to be used, enjoyed and owned — as a place to build a home or grow food or develop a park. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people consider the land differently.

Aboriginal spiritual identity and connection to the land is expressed in the Dreamtime. In Aboriginal cultures, the Dreamtime tells of the beginning of life. Different Aboriginal groups have different dreamtime stories, but all teach about aspects that affect daily life. Dreamtime stories teach Aboriginal people about the importance of sharing with and caring for people of their community, of nurturing the land and of the significance of the land and its creatures.

Dreamtime stories pass on the history of Aboriginal people, their relationship with the land and their spiritual connection. For Aboriginal people, their connection to the Dreamtime is still alive and vital today and will remain so into the future. The complex set of spiritual values developed by Aboriginal people and that are part of the Dreamtime include ‘self-control, self-reliance, courage, kinship and friendship, empathy, a holistic sense of oneness and interdependence, reverence for land and Country and a responsibility for others.11

The following diagram shows how, for Aboriginal people, all aspects of life are interconnected through the centrality of land and spirituality.12

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flags

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags are particularly important for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. The flags can indicate pride, show great respect and leadership and can enhance healing. The power of messages conveyed by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags should not be underestimated. Mainstream organisations that display the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags demonstrate their support for Aboriginal people and those from the Torres Strait Islands. Understanding the history and meaning of the flags, and displaying the flags appropriately is a step towards creating a culturally safe workplace for Aboriginal staff.

The Aboriginal Flag

Harold Thomas, an acclaimed artist, member of the Stolen Generations and a Luritja man from Central Australia, designed the Aboriginal flag. The flag was originally designed as a protest flag for the land rights movement of Aboriginal Australians. It is a symbol of identity, unity and Aboriginal rights.

The Aboriginal flag is divided horizontally into equal halves of black (top) and red (bottom) with a yellow circle in the centre. The black represents Aboriginal people. The red represents the earth, and spiritual relationships to the land. The yellow represents the sun, the giver of life and protector. Care should be taken to fly the Aboriginal flag properly, because grave offence has been caused when flags have been displayed upside down.

The Aboriginal flag was first raised in Adelaide on National Aboriginal Day on 12 July 1971 and was adopted nationally in 1972 when it was flown above the Aboriginal ‘Tent Embassy’ in Canberra. In 1995, the flag was proclaimed a ‘Flag of Australia’ under the Flags Act 1953, to reflect its increasing importance in Australian society.

The Torres Strait Islander Flag

The Torres Strait Islander flag was created as a symbol of unity and identity for Torres Strait Islander people. It was designed by the late Bernard Namok from Thursday Island. It was recognised by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission in 1992. In 1995, the flag was proclaimed a ‘Flag of Australia’ under the Flags Act 1953, to reflect its increasing importance in Australian society.

The Torres Strait Islander flag features three horizontal coloured stripes, with green at the top and bottom and blue in the centre, divided by thin black lines. The colour green represents the land, the blue the sea and the black represents Indigenous people. A white dhari (headdress) sits in the centre with a five-pointed white star beneath it. The dhari represents the people of the Torres Strait Islands. The star represents the five major island groups, and the white colour represents peace. Used in navigation, the star is also an important symbol for the seafaring people of the Torres Strait.13

Useful links and other information

(1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13) Source: VACCA Building Respect Partnerships 2010.

(2) AIATSIS Stolen Generations

(3) AIATSIS Apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples

(5) AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia

(8, 12) Source: Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency, September 2006, Working with Aboriginal Children and Families: A Guide for Child Protection and Child and Family Welfare Workers, Melbourne. Based on material from the NSW Office of the Children’s Guardian