It is one that integrates strong diagnosis(‘what is the cause of the problem?’) with appropriate decision making about the best response(‘is this best managed through adjudication by a third party, or can we resolve this better through mediation, a courageous conversation or facilitation?’).

A conflict resilient workplace does not rely solely informal dispute processes,but emphasises positive relationships and strong communication so that conflict is managed early, at the lowest possible level, and with the most appropriate response.

Conflict resilient workplaces share four features:

- Promote: They are proactive in building a culture of communication.

- Prevent: They stop things going wrong.

- Respond: They Respond Quickly and appropriately when things do go wrong.

- Comply: They comply with relevant guidelines, rules, regulations and address principles of natural justice and procedural fairness.

This guide uses terms such as grievance, conflict and dispute. These terms are evolving in conflict management literature (and in law), and therefore different organisations might use the terms indifferent ways.

‘Grievance’ in particular can be problematic, and senior HR managers have said that many staff see ‘grievance’ as an inevitable endpoint, requiring a third party adjudicator. Rather than prescribe definitions here, we urge you to interpret the language and terms we use here in a way that is meaningful to your organisation. Conversation and debate about the language of conflict resolution – in particular, what ‘conflict resilient’ means to you – can be a valuable part of the process leading to change.

Building an Integrated Conflict Management Model

Each workplace has its own culture, processes and traditions. This means that conflict management systems will inevitably look different in every organisation.

An integrated conflict management model should, however, link rights-based formal procedures with alternative dispute resolution models through strong interactive problem solving.

The people directly involved in the dispute should be actively encouraged and supported to take responsibility for managing their own issues.

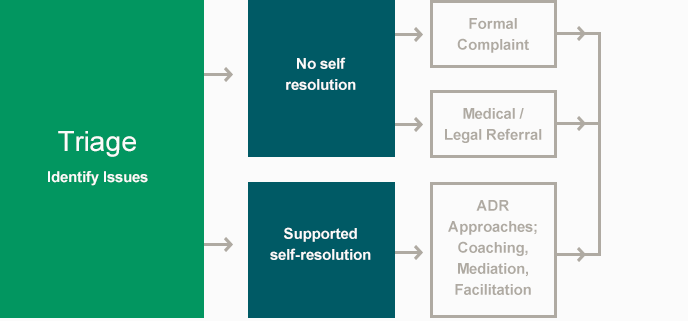

As Figure 1 shows, an integrated model is underpinned by strong collaborative intake assessment (triage) when disputes are raised. It encourages alternative dispute resolution which has a strong focus on the interests and needs of the parties concerned.

It has a place for formal grievance processes – but uses them for specific disputes suited to formal complaints, or as a safety net.

Characteristics of an Integrated Conflict Management Model

- Provides early intervention through a triage or collaborative intake assessment model with multiple entry points for ease of access.

- Identifies root causes of problems in addition to symptoms, and shares this information to create change.

- Uses alternative dispute resolution methods (feedback, conversation, mediation, facilitation) that preserve workplace relationships by:

- addressing the needs and interests of the people involved, not just formal

rights - encouraging self resolution (with support), rather than emphasising a formal arm’s

length process

- addressing the needs and interests of the people involved, not just formal

- Incorporates preventative actions such as training and awareness raising.

Figure 1: Integrated conflict management model

2.1 Triage: ‘What is the Real Issue?’

Organisations must have a strong intake assessment process for managing complaints and disputes. A triage system involves a skilled staff member (usually, but not necessarily from the Human Resources team) asking the right questions to determine: the root cause of the conflict, who is involved and the desired outcome. This helps people make an informed choice about the best resolution option. This process often goes under different names including collaborative intake assessment or triage (see Figure 1).

Through a triage process, it will for example, become apparent that if someone is accused of doing something that by policy and law must formally be dealt with, and if the other person clearly disputes that accusation, the appropriate process will be a rights-based process of adjudication. Here, a formal complaint is usually warranted.

Alternatively, if a dispute seems to have arisen through lack of clarity about issues (for example, where a person perceives someone’s behaviour as bullying), and if the dispute seems only to affect two parties, then mediation may be appropriate. If there is significant conflict, an intervention that transforms the conflict to the point where those affected are willing to cooperate would be appropriate.

These are the types of circumstances that can be raised through a triage process. It provides a legitimate opportunity for people to describe their particular issue. A trained intake assessment officer is able to ask pertinent questions. Options for resolving the issue, including the objective the person is seeking, as well as the likely outcomes, can be discussed. This collaborative approach results in people being better informed about their choices. It also provides people with a high level of ownership and responsibility for managing their own issues. In choosing to focus on interest-based processes, a person does not relinquish their rights.

However, in choosing to lodge a formal complaint based on rights, a person does relinquish control, as the process is usually beyond their control, and is often driven by a third party. Often people who seek some kind of redress are not made aware of this.

A triage process helps people to:

- define the problem and separate the problem from the person

- identify the roles and relationships that they have with each other and with the workplace;

- Identify the issues–personal, workplace, organisational, other

- Identify interests, needs and concerns (not just rights)

- unpack perceptions, assumptions, interpretations and expectations

- consider the impact of emotions on the process

- consider their own and others skills and communication styles

- identify the information needed

- explore options and alternatives

- communicate choices

- use objective criteria

- commit to change.

Multiple Entry Points

Ideally, the intake process will have multiple entry points. This encourages staff to act early and at an appropriate level when they have a concern.

For example, they could:

- self manage a concern by approaching a colleague directly

- seek internal advice from a supervisor, manager, human resources or elected Occupational Health and Safety representative

- seek informal resolution with assistance from a supervisor, manager or human resources representative

- seek formal resolution through a designated process (e.g. internal grievance)

- seek external advice(e.g. from the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission, or WorkSafe).

2.2 Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) processes – sometimes called appropriate dispute resolution processes – are an essential part of the integrated conflict management model.

They include approaches such as feedback, mediation, facilitation and conflict coaching –processes that can be used as an alternative to, or alongside, more formal, rights-based models. Figure 2 provides a list of some of the more commonly used approaches. These are described in more detail in Appendix A.

ADR processes and techniques are useful in managing a range of situations from individual performance to emotionally complex issues that can arise in working relationships. Recognising the best process for a given situation is critical and should be addressed early on, such as during the triage process. Figure 3 provides information on what approach might best fit a situation.

ADR methods are informal, voluntary and don’t include litigation. While they are usually structured, they can be non-adjudicatory.

Importantly, they are based on four key tenets, that:

- The best decision makers in a dispute are usually the people directly involved.

- To effectively resolve a dispute, people need to hear and understand each other.

- Disputes are best resolved on the basis of the people’s interests and needs.

- Disputes are best resolved at the earliest possible time and at the lowest possible level.

Figure 2: Commonly used ADR approaches to promote constructive relationships

| Feedback and interactive problem solving | Offering observations or helping someone to reflect. |

| Conversation | People talking to reach shared understanding and (possibly) commit to action. |

| Conflict coaching | Powerful questioning to help gain insights and encourage the concept of mutuality. |

| Mediation | A third party assisting the search for mutual understanding and optimal action. |

| Facilitation | A third party helping a group to achieve a collective goal. This could involve workplace conferencing or what is known as appreciative inquiry. |

Figure 3 distinguishes a range of different situations, and presents corresponding structured processes for responding constructively.

Figure 3: Using the best process for the situation

| Situation | Appropriate processes |

| Disputed accusation | Investigation + adjudication |

| Managers needing to respond appropriately to disputes and conflicts | Conflict coaching and other managerial skills |

| Disputes between two parties | Mediation (assisted negotiation) |

| Dispute or potential dispute between several parties | Facilitation (problem-solving, strategic planning, appreciative inquiry) |

| Specific conflict with no dispute or many disputes | Group conferencing, transformative mediation |

| General conflict across an organisation | Managed change Training, coaching, mediation, facilitation |

Why Use Alternative Dispute Resolution?

In most workplaces, conflict develops through everyday misunderstandings. Differences in style and expectations generate resentment, avoidance, aggression and other destructive thoughts, feelings and behaviours. The most strongly negative feelings associated with interpersonal conflict are anger, fear and contempt, which predispose people to disengage, or to engage destructively.

Once they are in a state of conflict, people identify others as the problem, cling to their own fixed positions, feel that they can only win if the others lose and insist on their own subjective criteria.

People in conflict find it hard to engage constructively until they have acknowledged the sources of the conflict, and have begun to transform conflict into cooperation. ADR approaches facilitate this kind of change in thinking and behaviour.

2.3 Where does this leave formal grievance processes?

Putting resources into alternative dispute resolution models does not do away with the need for grievance structures.

For example, certain situations demand formal processes be used: allegations of criminal or serious misbehaviour; situations where there is a lack of good faith and people won’t cooperate; situations where public policy, procedural or legal issues arise, or where the welfare of individuals is threatened.

There is widespread acceptance, and a legal requirement, that organisations must have fair and effective systems for handling grievances. If someone claims that a law or guideline has been breached, there must be an effective and fair system to test that claim. If a grievance handling system is not perceived as procedurally fair, it will itself generate grievances and become part of the problem.

A conflict resilient workplace uses adjudicated grievance processes when they are necessary but prevents conflict escalating into formal grievances when early resolution is possible.